Spark and Checkpointing

Introduction

Processing data with Spark on EMR is a challenge when clusters can be terminated at any moment. Below, I will discuss how to build a resilient data workload within this brittle environment.

Problem Statement

Imagine that you are working on a data workload which runs for 8 to 12 hours. Your organization uses AWS EMR to provision clusters and execute jobs. You are required to run the jobs using “spot instances”, which can save you up to 90% on cluster costs. However, the caveat with spot instances is that the cluster can be terminated at any time.

Fortunately, you can pick up where you left off if you persist your data to AWS S3.

An analogy for this problem is that you are playing a game where you need to drive through a desert to get from point A to point B. However, the wheels can fall off at any point, and when it happens you respawn at the last checkpoint. So, how should you choose the frequency of your checkpoints?

Solution

I recommend storing data at major stages of the workload. This is usually every 2 to 3 hours of processing time.

You might have multiple workloads running concurrently. That means that there is one job on the critical path. For that job, I reduce the increment to a checkpoint every 1 hour to further guarantee progression.

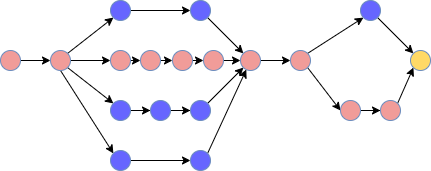

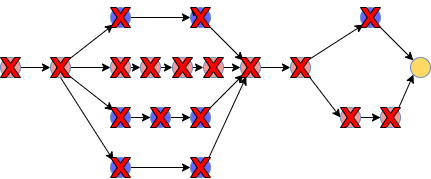

The figure below demonstrates the use case:

- The black arrows represent jobs.

- The blue circles represent checkpoints.

- The red circles also represent checkpoints except these are on the critical path. Thus, they are more frequent.

- The yellow circle represents the final output.

This approach yields a few benefits which can save your organization lots of money:

- Resumability: Recovering and resuming from the last point of failure.

- Self-healing: Avoiding OPS involvement.

- Cost Savings: Reducing reprocessing costs which can become significant when the spot market is unstable.

The Solution Creates a New Problem

You implement this solution – all is going well, and your EMR costs have reduced significantly. To your dismay, however, you realize that your S3 costs have spiked! Indeed, we chose to store data in favor of improving compute efficiency. This is a common trade-off in engineering.

S3 usage can explode because we are storing temporary “work-tables”. These work-tables are incorporated into the final output already. They are usually not needed once the final output is produced.

Hence, the second part of this solution is to clean up the data from S3 when it is no longer needed!

Under the hood, you could use either the “aws s3 rm —recursive” or the “hadoop fs -rm” command. I have found that the hadoop command runs 3x faster. Another alternative is to use S3’s lifecycle policies.

A Note About Testing

The challenge in testing is that it is invoked only during environment failures, so we have to think about simulating those failures in our test code.

For Unit Testing, we create a method to drop all tables. We use the method in the test runner at the points where we expect resumability to work.

import spark.implicits._

def dropAllTables(db: String) {

// ref: https://stackoverflow.com/a/44082786

val listOfTables = spark

.catalog

.listTables(db)

.select(col("name"))

.map(r => r.getString(0))

.collect

.toList

for(table <- listOfTables) {

spark.sql(s"DROP TABLE IF EXISTS $db.$table")

}

}The source code would need to invoke a directive to restore tables that are needed.

def restoreTable(db: String, table: String, path: String) {

val schema = spark

.read

.format("parquet")

.load(path)

.schema

spark

.catalog

.createTable(

tableName = tableName,

path = path,

source = "parquet",

schema = schema,

options = Map("path" -> path)

)

}For Integration Testing, validating every possible failure point is too cumbersome. Instead, we simulate the failure and recovery of one checkpoint using a shell script. The script will automatically perform the subsequent steps. First, we begin the spark job and cause a failure by requesting an unrealistically high value for executor memory. Spark will throw an allocation error and fail. We validate that the command failed by checking that the exit code is not zero. Then, we re-run the command using proper configurations. We observe that all validations are passing.

This test strategy allows us to test resumability, even though there may be many moving parts.

Conclusion

This approach has a high return on investment despite the additional engineering effort!